Reflections are important: they tell us who we are.

But, what happens when we don’t recognize ourselves in the reflection? My sense is that, typically, we try to change who we are to match what we’re seeing. And that this can have consequences.

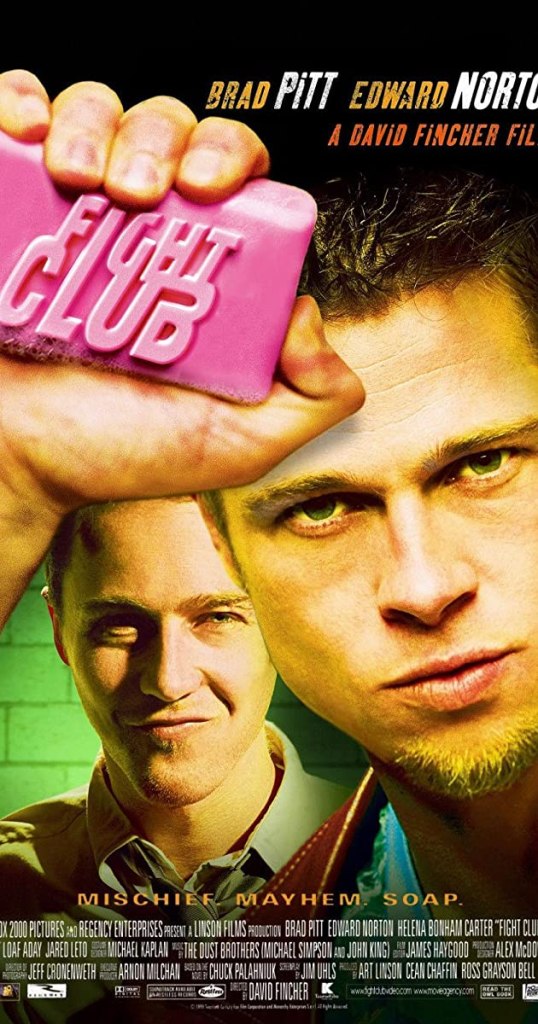

Case in point: Fight Club.

I saw Fight Club when it premiered in 1999, and I remember leaving the theatre feeling buoyant, exhilarated. The film seemed to describe my anxieties and frustrations to me. Tyler articulated everything I hated about late capitalism, in eminently quotable ways. He summarized the sick realization that much of what we do is motivated by maintaining social status: “Advertisements have [us] chasing cars and clothes, working jobs [we] hate so [we] can buy shit [we] don’t need.” His mantra—“You are not your job. You are not how much money you have in the bank”—was a necessary corrective to the rampant careerism that was foisted upon us. He even pinpointed the sense of expectation and frustration that described so many of my generation: “We were raised by television to believe that we’d be millionaires and movie gods and rock stars—but we won’t. And we’re learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed-off.” Jack’s job as a recall coordinator encapsulated the devaluation of human life in an economy fixated solely on corporate profit, as well as the pernicious nature of much of the employment we were encouraged to accept: “Take the number of vehicles in the field, (A), and multiply it by the probable rate of failure, (B), then multiply the result by the average out-of-court settlement, (C). A times B times C equals X. If X is less than the cost of a recall, we don’t do one.”

The film forcefully drove home just how fundamentally society was failing us: in conjunction with growing awareness of the great crises that loomed over us (climate change, pollution, deforestation, globalization, economic inequities, racism—the list is endless), it contributed to a sense of wary watchfulness, as if everyone was waiting for something to break.

If the film’s analysis of late capitalism is straightforward enough, Tyler’s solution was more contentious. Both Fight Club and Project Mayhem were seen by many critics as being proto-fascistic. A recent retrospective article on the film connects it explicitly with current authoritarian, misogynist and racist movements. And, to the extent that the film did diagnose a real discontent with life inside the Overton window, the footage of the Capital Riots on 6 January 2021 would seem to prove this interpretation to be correct. Many—but not all!—of the rioters seemed to come from the segment of the population that made up Fight Club (the people, as Tyler says, who “do your laundry, cook your food and serve you dinner”). Moreover, they were challenging the entrenched power of the elite and—whether aware or not—demanding the overturning of democracy and the instatement of something resembling fascism.

But, do we have to understand Fight Club as fascist? And, more importantly, would our political landscape be different now it we chose not to view it through that particular lens? The film begins with an evocation of the insulated, consumerist life of late capitalism: Jack lives in near-total isolation in an apartment building with foot-thick cement walls and has, as he says, become a “slave to the IKEA nesting instinct.” Fight Club is invented as a remedy to this condition. Although reviewers focused on the violence, the emphasis on all the scenes involving fighting isn’t on inflicting punishment but on receiving pain. And this pain is an effort to become un-numb to reality. With Duke Senior in As You Like It, Jack could characterize the blows as “counsellors / That feelingly persuade me what I am.” The impulse is instinctive—not political in itself, but subject to political interpretation.

The significance of Project Mayhem is more complex. Immediately, its objective is to destroy all records of debt, but Tyler intimates that his long-term ambitions are more ambitious:

In the world I see–you’re stalking elk through the damp canyon forests around the ruins of Rockefeller Center. You will wear leather clothes that last you the rest of your life. You will climb the wrist-thick kudzu vines that wrap the Sears Tower. You will see tiny figures pounding corn and laying-strips of venison on the empty car pool lane of the ruins of a superhighway.

This describes a return to a hunter-gatherer economy. And, one does not have to spend much time on the internet to discover an increasing number of people see this way of life as being better and healthier than our modern world. But again, this impulse can’t be easily mapped onto the traditional left-right political spectrum.

So, this is, finally, the question. Did the fact that critics called the protest against late-capitalism in the film fascistic actually make it in reality fascistic? Or, to put it another way, did a number of people who had—arguably legitimate—grievances with the existing order become the fascists the reviews described because that was the reflection of themselves that they were shown by culture?

To what extent are we all scripted?