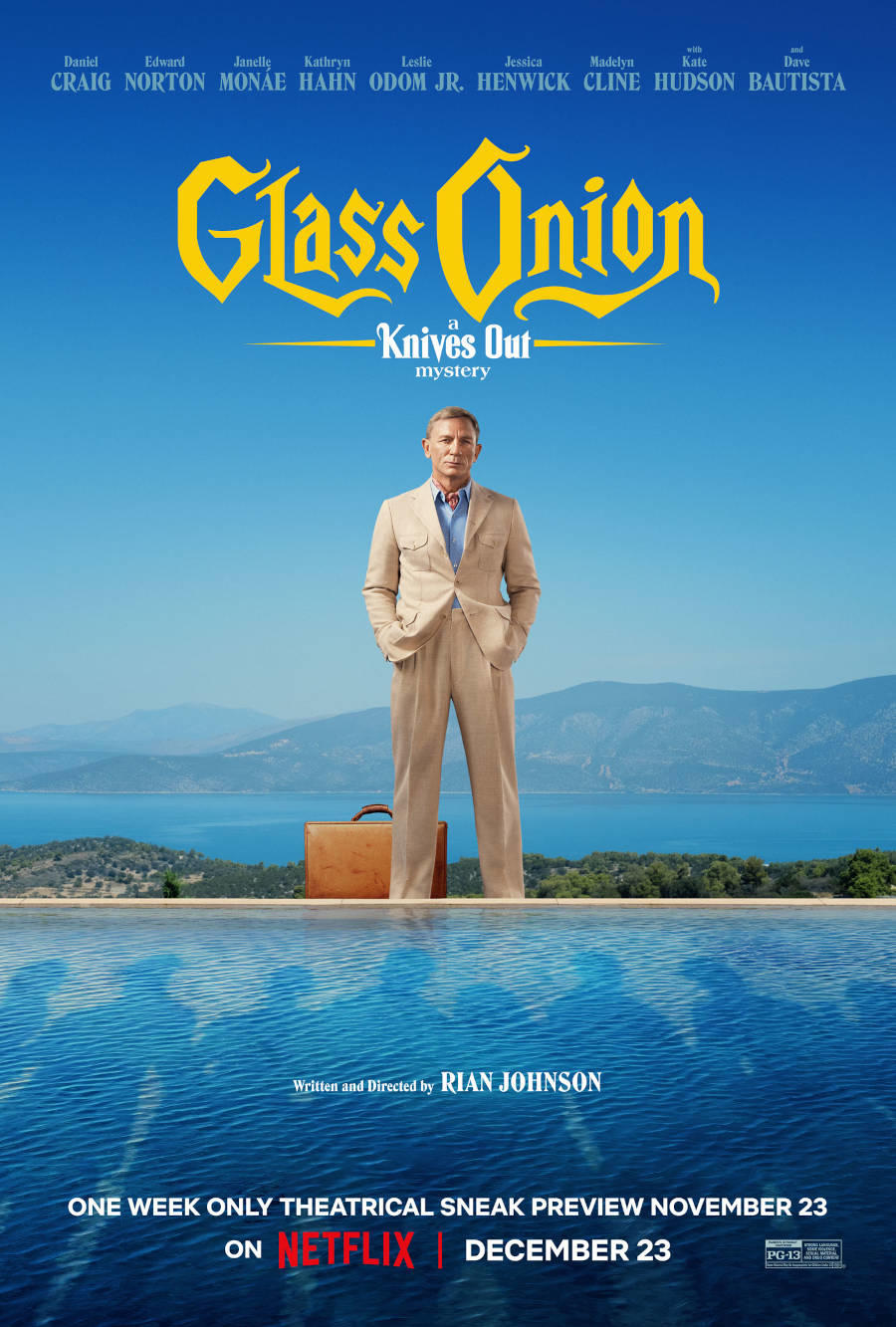

One of the things fiction does is to help us understand reality, and by this metric Glass Onion (Rian Johnson, 2022) provides a great service. Having grown up during the tech boom but also being old enough to remember another time, I’ve been continually shocked by the blind worship of digital entrepreneurs, as well as the unthinking celebration of insane wealth accumulation and the social disruption that destroyed whole industries.

This is why the depiction of tech billionaire Miles Bron matters. Miles is an amalgam of a variety of prominent tech heroes who have been uncritically praised. By revealing Miles to be an actual idiot who his stolen his successful ideas and who, if not stopped, may well destroy the world with an unstable energy source, this film contributes powerfully to the current cultural revaluation, in which such figures are increasingly viewed as dangerous megalomaniacs who in fact do profound harm.

The willingness of Miles’ associates to repeatedly lie for him, even when his newest idea may lead to actual cataclysm, underscores how the system is incapable of reforming itself, because people with the power to intervene are too much part of it that system to challenge it.

And before reading further, be forewarned that I don’t know how to write about movies without including EVERY SPOILER THAT EXISTS.

In the first Knives Out installment (2019), Johnson explores the issue of class privilege in current culture. Harlan Thrombey, a successful mystery writer, has a large family of children and grandchildren, whom he has aided in various ways. The problem is not that he has done this—it’s natural for parents to help their children—but rather that his offspring persist in believing that they are, as is repeated several times in the film, “self made.” It is this ideology that is destructive. Because they won’t acknowledge the extent to which they’ve been supported, they perpetuate the destructive creed that their wealth is the product of merit, and they label those who have not had such success as inferior.

Glass Onion extends this analysis. Miles owes his accomplishments to a combination of factors and social connections, the least of which is his own ability. Because of his power and wealth, however, he is considered a genius and is afforded the credibility to shape world affairs

Alpha Corporation, Miles Bron’s company, was the brainchild of Andi Brand. When Andi’s sister, Helen, describes its genesis, she explains that Andi collected a random group of friends whose careers had stalled in different ways, but in whom she apparently saw some kind of potential. Then she adds Miles to the mix. What she expects from him again isn’t made clear, but things begin to happen. One friend wins a local election and kicks off a political career, the second starts to publish scientific papers, the third has a successful fashion show and the fourth becomes a successful Twitch streamer. The implication is that Miles somehow catalyzes this.

Miles’ initial appearance suggests his role: his long hair, red shirt and leather vest are virtually identical to Tom Cruise’s T.J. Mackey in Magnolia (1999). This may, of course, be some Hollywood insider joke, but I like to think there’s more to it. Mackey is a motivational speaker. If Andi brought Miles in as a motivator, that would explain the general rise in fortune.

Andi then has the idea for Alpha Corporation. Alpha is called a “tech giant” in the film, and seems to be involved in everything from cars to television. Miles stays with her, possibly as some kind of hype master. When Andi and Miles have a falling out over his interest in a dangerous new energy source, however, he’s able to wrestle control of the company through what Benoit calls the “sheer dumb force” of his “machine of lawyers and power.”

The phrasing is significant. Through serendipity and his willingness to press advantage, Miles ends up in control of a powerful business juggernaut. Certain of his brilliance, he bombards his scientists with ridiculous ideas (“Uber for biospheres,” “AI in Dogs = discourse”), insisting that they be made viable. One success illustrates how the process works. Miles’ sends a fax stating “CHILD = NFT,” which is then transformed by some unnamed team into the “Krypto Kidz” app. Now, obviously, these ideas are only tangentially related, and the real creative and technological accomplishment is to first imagine how the phrase could be made an actual product, and then to build and market it. However, that work is overlooked, and the accomplishment is ascribed to Miles’ genius, which further reinforces his status.

Great success is always mysterious. We want to believe that it’s a function of merit, because that seems fair, but we all know too many talented, ambitious, hardworking and unsuccessful people for this to be a viable position. We also all know seeming idiots who are quite successful. Recently attention has been paid to the Nepo baby phenomenon, and this is certainly significant.

One factor that doesn’t get much consideration, however, is the role that simple luck plays. A computer experiment (“Talent vs Luck: the role of randomness in success and failure,” Advances in Complex Systems, 2018) tracked the careers of simulated individuals over a forty year period. Their individual talents (defined here as any combination of “intelligence, skill, motivation, determination, creative thinking, emotional intelligence, etc”) varied, and every six months the subjects received random assignments of either lucky or unlucky events. The experiment concluded that “the most talented individuals were rarely the most successful,” “mediocre-but-lucky people were much more successful than more-talented-but-unlucky individuals,” and “[t]he most successful agents tended to be those who were only slightly above average in talent but with a lot of luck in their lives.”

Miles’ is lucky because Andi befriends him. His talents—if you can call them such—are his self-confidence, his capacity for self-promotion and his utter ruthlessness. Unfortunately, such people often rise to the top of corporations. The great error is for the rest of us to believe that they are especially smart or talented.

The two Knives Out films can be seen as developing a theme that emerged in Johnson’s lone Star Wars movie, The Last Jedi (2017). One disturbing aspect of the Star Wars saga is how it increasingly became a family drama. The Skywalker clan is dominant—eventually leading both the empire and the resistance to it—because, in the series’ mythology, their bloodline is simply superior. And this was quite literal: Skywalker blood had an exceptionally high midi-chlorian count, which is a physically inheritable trait. Of course, however, positing a family that is better than everyone else because of their blood is fundamentally eugenic and literally monarchical.

Whatever else we want to say about The Last Jedi, at least it challenges this orthodoxy. The fact that Rey is initially conceived as “nobody” from “nowhere” undermines this tacitly assumed idea of natural hierarchy, and the final scene, showing a child moving a broom with the power of his mind, suggests that even the Jedi philosophy is just one interpretation of a basic power that is generally available and open to different readings.

Now we just need a movie where Benoit Blanc investigates how Emperor Palpatine was able to return to life in The Rise of Skywalker after clearly dying at the end of The Return of the Jedi.