Fiction is a reflection of its era. Current political and social events heighten our awareness of particular issues, and this affects both how our criticism interprets the narratives of the past and how our own stories interpret reality..

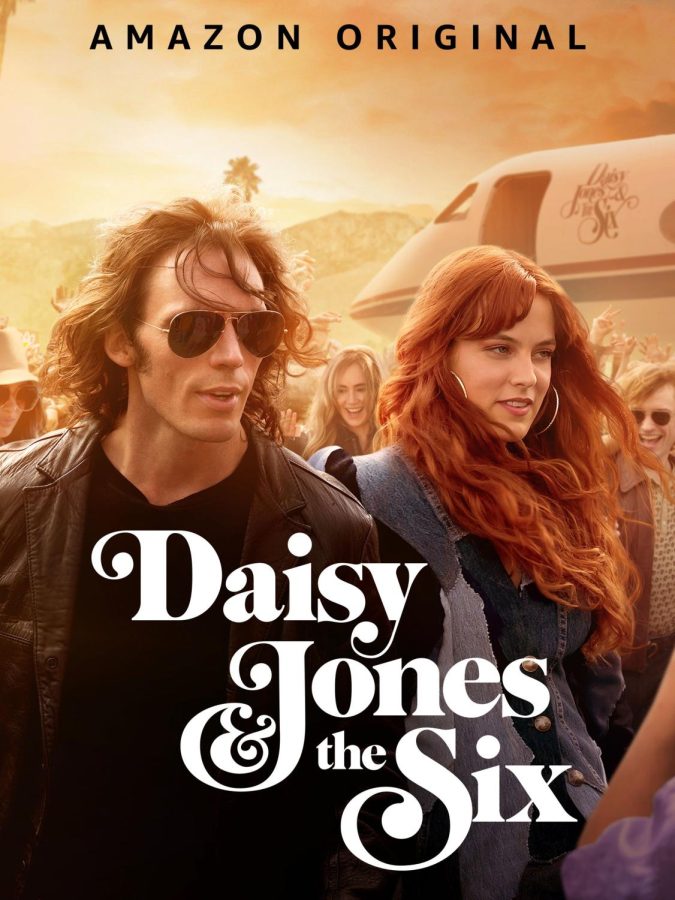

All of this is a long-winded justification for writing about Daisy Jones and the Six. I feel I need to do this because the fictional band in that series is loosely modeled on Fleetwood Mac, and I am not now—nor have I ever been, nor can I imagine a time that I ever will be—a fan (at least of the post-1974 iteration). However, the series acutely illustrates how the fictional interpretation of history overwrites reality to express the values of its time, and this is something I can’t pass up.

And I should be clear here that I’ll be discussing the television series, not the novel upon which it is based, and I will, as per usual, provide EVERY SPOILER UNDER THE SUN.

The inspiration for Daisy Jones and the Six occurred, as one would expect, at a Fleetwood Mac concert. Taylor Jenkins, the author the novel upon which the series is based, wrote:

It is that moment, more than anything else that is foundational for the fictional creation. Jenkins noted that “almost nothing in the book actually happened with Fleetwood Mac–it’s a Fleetwood Mac vibe but it’s not their story. I haven’t actually ripped off their lives, . . . I just wanted to spend more time listening to Rumours and needed a good reason to do it.”

From this perspective, then, Daisy Jones and the Six is an effort to imagine how a band like Fleetwood Mac and an album like Rumours came into being.

The real Fleetwood Mac has a very complicated history: beginning in 1967 as a blues band, it went through a series of rapid personnel changes (involving many of the luminaries of British rock) until 1974, when it relocated to California and Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks joined Mick Fleetwood, John McVie and Christine McVie to form the classic lineup that most Fleetwood Mac fans recognize. This iteration also demarcated the band’s transition to its distinctive brand of California rock. The cast has continued to rotate, however, and, as of now, eighteen musicians have been played in it. In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that I learned all of this from Wikipedia.

The entangled private lives of the band members are legendary. Past member Bob Weston left the band after an affair with Mick Fleetwood’s wife, Jenny Boyd. Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks were in a relationship when they joined the band, but subsequently broke up and Nicks had a brief affair with Mick Fleetwood. John and Christine McVie also divorced, and Christine had an affair with the band’s lighting director. This is merely the tip of the iceberg. Substance abuse was also a persistent factor (these are also Wikipedia facts).

A history this complicated requires radical simplification, and Daisy Jones and the Six defaults to established archetypes to represent the creative energies of rock bands: singers and lead guitarists are typically imagined as the “brains” of the band, coming up with the songs and lyrics; drummers are comic figures who are just there for a good time; bassists are bitter because they aren’t guitarists; and keyboardists are inscrutable.

The odd creative decision, however, was to make the story about the importance of family.

In Daisy Jones, the band consists of a group of musicians from Pittsburgh, led by Billy Dunne. After some local success they relocate to Los Angeles and get a recording contract. Billy’s wife, Camila becomes pregnant and they marry. During their tour, Billy, feeling intense pressure, begins drinking heavily, has a number of assignations with groupies and eventually is confronted by his wife. Deeply ashamed, he enters rehab and briefly quits music altogether.

The band regroups, then experiences massive success when Daisy Jones joins and she and Billy start writing songs together. The sexual tension between Billy and Daisy becomes increasingly difficult to control, however, and on one occasion they kiss. Billy’s brother, Graham, begins a relationship with Karen, the band’s keyboardist.

On one crucial day, all of these stresses come to the fore. Camila confronts Billy about his emotional infidelity, which prompts him to begin drinking again. Karen, who became pregnant, tells Graham that she had an abortion because she wants a career in music; and Eddie, the bassist, reveals to Billy that he has had an affair with Camila. Daisy, aware of the bond between Billy and Camila and what their separation would do to him, urges him to reconcile with his wife.

Obviously this summary excises the drama of the series, but highlights what I can only term its strange puritanism. It describes a world where family is not simply of primary importance, but the only thing that matters. Although Billy and Daisy write better songs together than either can on their own, they must part ways to preserve Billy’s marriage. The band dissolves, with the strong suggestion is that this is the right decision. The series is set up like a documentary, in which the characters are interviewed many years after the band breaks up: in the final episode the two band members who continued to pursue musical careers—Karen and Eddie—appear diminished; Billy and Graham, who prioritized family, are shown living rich, fulfilling lives.

All of this, of course, contrasts strongly with the actual Fleetwood Mac, who, despite all kinds of messiness and emotional turmoil, continued to make music together, presumably because it was important to them. This is also, I believe, where the series reflects the current zeitgeist, or at least some aspect of it. Artistic achievement, which I remember as having a great deal of importance, is marginalized, and the music that Daisy Jones and the Six may have made if they had continued to collaborate doesn’t seem to matter much.

The value that art has is what is afforded it by culture, and so it changes with that culture. Once, when William Faulkner was about to get drunk, his daughter asked him not to, and he refused by saying “No one remembers Shakespeare’s child.” Seemingly he thought this response satisfactory, although now it provokes disgust. The alternative, however, is the grimace on Billy’s face as he self-censors his music and joylessly white-knuckles his way through sobriety and faithfulness because of familial obligations.