One of the loose themes of this blog is how fiction often fails to mediate reality, and so I’m going to write about the last season of The Crown, specifically the representation of the events leading to Diana’s death. My interest in the Royal Family is limited, but my interest in interpretation is real, and this episode encapsulates some of the problems that can emerge when history is fictionalized.

In season six, episode two, Diana has begun a relationship with Dodi Al Fayed, which has been largely engineered by Dodi’s father, Mohamed. Mohamed is represented as being anxious to win a place with the Royal Family, and to that end wants his son to marry the former Princess of Wales. To speed matters along, he leaks the couple’s location to a photographer, Mario Brenna, who captures an image of them embracing on a yacht. The photos sell for an unprecedented sum, and paparazzi interest in Diana, already intense, goes into overdrive with the realization that the right picture can earn a life-changing fortune.

The next episode describes the frenzy that ensues as larger and larger crowds follow Dodi and Diana. Again to expedite the relationship, Mohamed orders his son to bring Diana to his house in Paris, somehow assuming that his meeting the couple there will lead to their engagement. In a dense city and traveling by car, Diana is hunted: her increasingly erratic behavior, the escalating tensions of her bodyguard staff, and the continued siege by the photographers and fans lead to the fatal high-speed car crash in the tunnel.

While her death is a tragic accident, Mohamed Al Fayed is made to bear substantial responsibility, having put the ghastly train of events into motion solely for his own self-aggrandizement.

Except it’s very unlikely that this is what happened. The identity of the person who gave the information to Mario Brenna is not known. Brenna claims that he discovered the location of the yacht himself, which of course is possible. Tina Brown, however, has said that the source was most likely Diana: at this time her relationship with the surgeon Hasnat Khan had ended, and she wanted to make him jealous. The idea that Mohamed provided the information seems to exist only inside the world of The Crown (Brenna himself has called the idea “absurd and completely invented”).

So, why tell the story this way? We can never know why storytellers make the decisions they do, but I think it is because the series wanted to give us a simplified, sanitized portrait of Diana, one in which she is depicted primarily as a mother who loves her children and is trying to pull her life together to better help others. The Diana who had numerous affairs (many of whom were married men) and would work with the paparazzi to further her own ends doesn’t cooperate with this image, so that dimension is excised from the representation.

The crueler decision, of course, is to defame Mohamed Al Fayed, which has rightly led to the series being charged with racism.

Pointing out these falsehoods will invariably elicit the comment, “You know it’s a show, right?” This is true, but I also believe that shows are important because they influence how we understand reality. It isn’t a great stretch to argue that a series made in and for the West will, by representing Arab characters as duplicitous and underhanded, work to perpetuate racist assumptions.

And this is merely one of many, many such inventions.

Margaret Atwood has outlined the rules she followed for writing her historical novel, Alias Grace. If there was “a solid fact,” she “could not alter it,” and “every major element in the book had to be suggested by something in the writings about Grace and her times.” However, “in the parts left unexplained—the gaps left unfilled—[she] was free to invent.” Invention is necessary to fill in the gaps to transform historical record into coherent narrative, and it is essentially conjectural. However, this conjecture must be grounded on fact for the creation of historically liable narratives. The Crown is, obviously, not Alias Grace, but it is described as a historical drama, and this carries the assumption that it’s giving viewers something approximating actual history.

Simon Jenkins has pointed out that fake history is “fake news entrenched.” The depressing factor here is that much of this seems to come down to a cynical disregard for historical record. Rather than using its immense resources to give us complex, multifaceted characters, or to condense complicated situations in dramatically effective but responsible ways, the series defaults to easy, fallacious tropes and stereotypes. These add to our collective misunderstandings—and our collective grasp of reality becomes weaker.

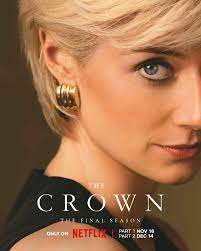

I Think Elizabeth Debicki would be great choice as Wonder Woman/Princess Diana of Themyscira In DCEU

LikeLike